‘“What have I done now? – on a studio visit with Marja van Putten

Interview February 3, 2025, by Alex de Vries

That Marja van Putten (b. Rotterdam, 1956) would become a radical feminist who would would advocate for activist emancipation from Amsterdam squatters’ strongholds was not written in the stars. Nor that she would develop a considered practice as a visual artist after those distinctly those formative years. She was born into a Reformed family in Rotterdam’s Oude Noorden neighborhood where social control within a closed community was intense. Even wearing pants was considered shameful for a girl.sculptural. In her artistry she has left that judgment on behavior and lifestyle far behind with work that is at once systematic and playful, well thought out and tidy, ordered, agile, personal and free.

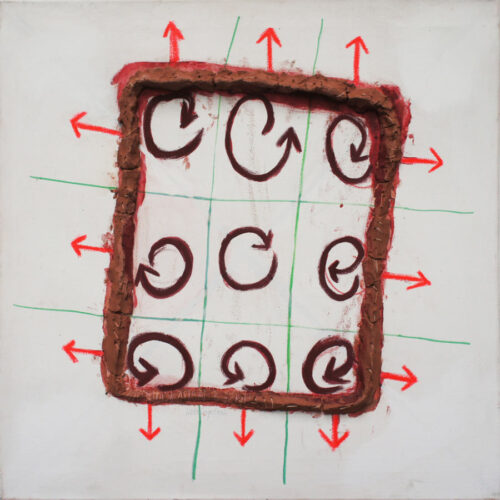

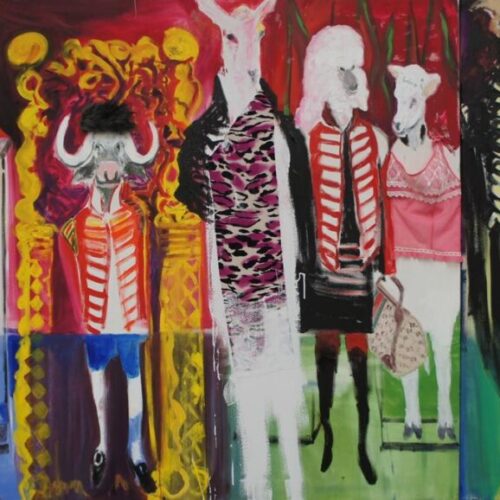

Marja van Putten is first and foremost a painter, a fundamental painter even, who systematically subverts precisely visual order in a fixed grid of nine boxes on her canvases. Yet her recent presentation femmeBRUT 3D in November 2024 in art space the Bouwput on the Ferdinand Huykstraat in Amsterdam-West – with the motto Anarchy in a white cube – took the form of a sculptural installation. In a motley array of colors, with figures made of textiles and other materials forming a varied crowd like those you might encounter on a busy day at the Albert Cuyp market.

As a visitor, the theatrical setting gave me the idea that I was confronted with myself in a situation that, although I had chosen it myself, I was being subordinated to it against all odds; as if I had stumbled into a throng of pogoing punks at a concert. These textile works refer to traditional craft forms – crocheting, knitting, embroidery, weaving, lace-making – which have long ranked low in the hierarchy of art as forms of feminine craftsmanship, and which, as a painter, she reinvigorates in imaginative, bold and uninhibited elaboration.

‘I myself am becoming more and more normal,’ says Marja van Putten, ‘but my work is getting crazier.’ In our family of four children, there was always the pressure of the immediate family in the three streets that surrounded us. My father and mother were actually not so strict in doctrine and did try to steer clear of Reformed precepts, though not openly. They were more progressive than their immediate surroundings. My father had an office job, but much more importantly, he played the piano at home every day. His musicality gave me an idea of free thought and imagination.

At one point we moved to a new housing estate near IJsselmonde with the desolate atmosphere of Alex van Warmerdam’s film De Noordelingen. But at least we had left that reformed community.

That said, six of my classmates in grammar school went on to study theology, while I was considering art history. Art history was my eighth subject in grammar school, but after the initial question “What is art?” which fascinated me, Ernst Gombrich’s Eternal Beauty was mostly about boring architectural styles and a division into art movements. It was a time when I saw all kinds of social changes around me: girls were walking in hotpants and lying on the beach in bikinis, while at the same time that contradictory religious milieu determined my daily life. I wore hotpants myself, but inwardly it was not right. I went to the teacher training college for drawing and handicrafts N.L.O. in Delft where I graduated in 1982 with a thesis on feminism in art.

Marja van Putten had always tried her best until graduation and she made short work of that. She left for Amsterdam and threw herself into the feminist squatting movement. For three years she was fully active in this politically conscious subculture. She was co-editor and designer at the Women’s Weekly, an anarchist collective, taught courses in a women’s handyman business and was much in evidence at the C.O.C.

“In those days I lived by the motto ‘don’t be afraid of fear.’ Actually, I didn’t dare go out on the streets alone at night in Amsterdam, but did it anyway.

As time went on, I discovered that within the squatting movement there was a battle of directions based on strict views that reminded me of my Reformed youth. Within that pigeonholing, groups fought each other, even to the point of fighting. There was a continuous framework of judgment that you had to meet and were called to account for. Everything you did or said was questioned. I had to free myself from that. Don’t get me wrong, I am not vindictive. I became someone through the squatting and women’s movement.

In Delft I had already seen new possibilities being developed in painting. I needed that nuance and went to evening classes at the Rietveld Academy. I was 28 and five years later I graduated and was able to begin my professional practice as an artist at 33. I received a basic grant from the Visual Arts Design and Architecture Fund in 1994, bought a van and traveled around Finland, Estonia and France as a free artist with a life of adventure.

I used up that scholarship in a year and a half, whereas you had to live on it for at least two years. So I ran out of money, but through connections I got the opportunity to do the “preliminary work” for Armando’s bronze sculptures, as he called them. In a number of steps I made a model based on a drawing of his hand and from that a sculpture in clay. I did that for almost twenty years, starting in 2005 together with Wim Vonk.

At the same time Arttrust, my company in web design & graphic design, came into being. So since 1996 I have been self-employed, which is very well combined with making my art.

In the early days it all happened in my studio in Amsterdam East, including the making of the sculptures. Until 2006 when I started sharing my studio in large anti-squat sheds with Wim Vonk.

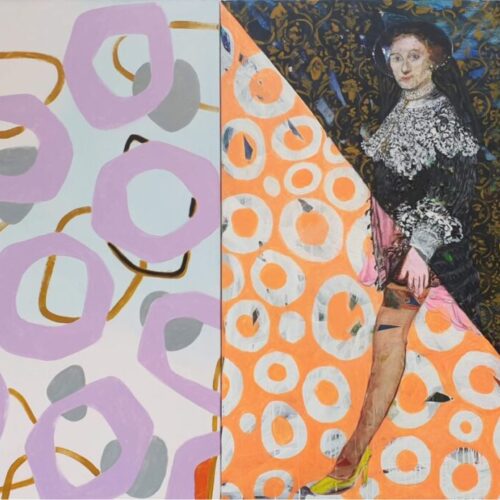

Inspired by artists like Eva Hesse, who followed a distinctly personal direction within fundamental painting as a woman, Marja van Putten developed her own system within her paintings. Influenced by the novel The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, in which a woman searches for personal, professional and political identity in an environment in which she is opposed by betrayal and rejection, she searched for the importance of her own painterly imagination.

To do so, she also delved into aspects of painting that she disliked. For example, she had a love-hate relationship with Mondrian’s work and view of neo-plasticism. Eventually she arrived at an arrangement in her paintings in nine compartments that she divided into three basic colors: red, green and white, and contrasts such as inside and outside, inner and outer, hard and soft. It was not a system for the sake of the system, but a handhold to give her paintings compositional dynamism.

‘In fact, the system undermines itself. It implodes. I am thrown back onto myself, confronted with the question of who I am and what I do. I have given it many uses—in abstract paintings, but also in artist’s books. For me it is a kind of coding, precisely in order to escape coding and strive toward openness, toward progress. By continually rising up I resist being pushed down. By painting this way I astonish myself: what has emerged this time, what have I done now, where did it come from? In this way my work becomes ever stronger and more extreme. In 2022 I created a major exhibition at Loods 6 in Amsterdam. That was the first femmeBRUT exhibition: large canvases two by two meters in size, made of textile and occasionally some paint.’

For years Marja van Putten made paintings with, as she herself says, ‘things on them./ She eventually felt she had exhausted painting in every possible way. She asked herself what else she could create beyond a painting: when is it still a painting? She recalled the traveling international group exhibition Sensation that she had seen in London in 1997, and especially the work of Chris Ofili, who made paintings using elephant dung.

She changed course and three years ago began her femmeBRUT 2D works, and over the past year the textile sculptures of a group of figures with diverse backgrounds and characters—figures to which she relates personally, as to the social network of freethinkers she has gathered around her in art. Where this new beginning will take her now that she has just turned 68, she does not yet know: “I don’t know how it will continue,” she says, “but one thing is certain: she is unstoppable.